MC1000 8通道藻类培养与在线监测系统由8个100ml藻类培养试管、水浴控温系统、LEDs光源控制系统及光密度和溶解氧(选配)在线监测系统等组成,可用于藻类培养与控制实验、梯度对比实验等,适于水体生态毒理学研究检测、藻类生理生态研究、水生态研究等,其主要功能特点如下:

1. 8通道藻类培养,每个藻类培养试管可培养85ml藻液

2. LEDs光源,可对每个培养试管独立调节控制和设置光强度和时间,如昼夜变化等

3. 光密度在线监测,包括OD680、OD735,监测数据自动存储

4. 溶解氧在线监测(备选)以测量分析藻类光合作用等

5. 温度、光照控制可用户设置不同的程序模式

6. 气泡混匀:可通过调节阀手动调节气流量以对培养试管内的藻类进行混匀

7. 可选配O2/CO2监测系统,在线监测藻类光合放氧和CO2吸收

8. 可选配藻类荧光测量模块

应用领域:

l 多通道同步藻类培养

l 同步梯度胁迫实验

l 培养条件优化

l 控制培养条件与藻类生长动力学监测

仪器型号:

MC 1000:仅进行藻类培养,不能监测OD

MC 1000-OD:可同时进行藻类培养和OD监测

技术指标:

1. 藻类同步培养通道:8个

2. 培养管容量:100ml,建议培养容量85ml

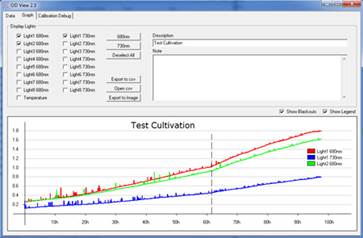

3. 在线即时监测参数:分别监测每个培养管的OD680和OD720,数据自动保存到主机内存中,PIN光电二极管监测器,665-750nm带通滤波器(MC 1000-OD)

4. OD测量程序:将主机内存中的OD数据下载到电脑中并以图表形式显示,数据可导出为TXT或Excel文件

5. 精确控温范围:标准配置20℃ - 60℃,可选配置15℃-60℃(需加配制冷单元)

6. 加热系统:150W筒形加热器

7. 水浴体积:5L

8. 水浴自动补水模块(选配):水浴水位因蒸发降低后可自动补水

9. 光源系统:光强0-可调,冷白光LED(标配),强度可达900μmol/m2/s;暖白光LED(可选),光强可达750μmol/m2/s;其他颜色LED可定制

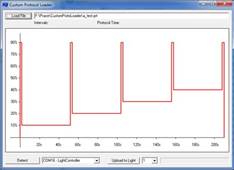

10. 控光模式:可静态或动态设置光照程序,如正弦、昼夜节律、脉冲等;可选配用户自定义程序,支持用户编辑多达224步的不同光强和持续时间的光周期

11. 控制单元显示屏:可调控培养程序和显示数据

12. 气流调控:通过多管调节阀对8个培养管手动独立调控气体流量

13. PBR实时在线监测分析软件(选配):

a) 通过PBR软件动态调控光照和温度模式

b) 通过光密度(OD680、OD720)变化实时监测藻类生物量

c) 对生长速率进行实时回归分析

d) 多数据管理功能(过滤、查找、多重导出)

e) 可将测量数据、培养程序和其他信息保存到数据库中

f) 通过GUI图形用户界面设置培养程序并在线显示测量数据图

g) 数据可导出为CSV、Excel或XML文件

14. GMS高精度气体混合系统(选配):可控制气体流速和成分,标配为控制氮气/空气和二氧化碳,气源需用户自备

15. O2/CO2监测系统(选配):8通道续批式监测藻类CO2吸收或光合放氧通量:

a) 氧气分析测量:氧气测量范围0-100%,分辨率0.0001%,精确度优于0.1%,温度、压力补偿,数码过滤(噪音)0-50秒可调,具两行文字数字LCD背光显示屏,可同时显示氧气含量和气压

b) 二氧化碳分析测量:双波长非色散红外技术,测量范围0-5%或0-15%两级选择(双程),分辨率优于0.0001%或1ppm(可达0.1ppm),精确度1%,通过软件温度补偿,具两行文字数字LCD背光显示屏,可同时显示CO2含量和气压,具数码过滤(噪音)功能

c) 气体抽样与气路切换:具备隔膜泵、气流控制针阀和精密流量计,气路自动定时切换功能

16. 藻类荧光测量模块(选配):用于测量藻类荧光参数以反映藻类生理状态及浓度,荧光测量程序包括Ft,QY,OJIP-test,NPQ、光响应曲线等,可选配探头式测量或试管式测量:

a) 探头式测量:具备光纤测量探头,可插入培养液中原位测量藻类荧光参数

b) 试管式测量:具备测量杯,可取样精确测量藻类荧光参数及光密度值

17. 通讯方式:RS232串口

18. 尺寸:71×33×21 cm

19. 重量:13kg

20. 供电:110-240V

应用案例:

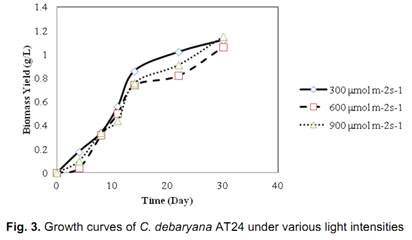

不同CO2浓度下衣藻Chlamydomonas的生长曲线(Zhang,2014)

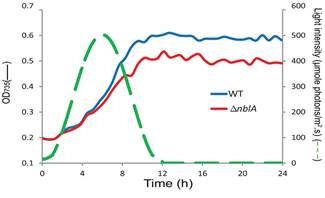

聚球藻Synechococcus野生型和△nblA的生长曲线(Yu,2015)

产地:捷克

参考文献:

1. Yu J, et al. 2015. Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973, a fast growing cyanobacterial chassis for biosynthesis using light and CO2. Scientific Reports 5:8132, DOI: 10.1038/srep08132

2. Grama B S, et al. 2015. Balancing photosynthesis and respiration increases microalgal biomass productivity during photoheterotrophy on glycerol. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01544

3. Davis R W, et al. 2015. Growth of mono- and mixed cultures of Nannochloropsis salina and Phaeodactylum tricornutum on struvite as a nutrient source. Bioresource Technology 198, 577-585

4. Patzelt D J, et al. 2015. Hydrothermal gasification of Acutodesmus obliquus for renewable energy production and nutrient recycling of microalgal mass cultures. Journal of Applied Phycology, 27(6), 2239-2250

5. Patzelt D J, et al. 2015. Microalgal growth and fatty acid productivity on recovered nutrients from hydrothermal gasification of Acutodesmus obliquus. Algal Research 10, 164-171

6. Flowers J M, et al. 2015. Whole-Genome Resequencing Reveals Extensive Natural Variation in the Model Green Alga Chlamydomonas reinhardti. The Plant Cell 27(9), 2353-2369

7. Makower A K, et al. 2015. Transcriptomics-aided dissection of the intracellular and extracellular roles of microcystin in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81(2), 544-554

8. Vu M T T, et al. 2015. Optimization of photosynthesis, growth, and biochemical composition of the microalga Rhodomonas salina—an established diet for live feed copepods in aquaculture. Journal of Applied Phycology, doi:10.1007/s10811-015-0722-2

9. Nikolaou A, et al. 2015. A model of chlorophyll fluorescence in microalgae integrating photoproduction, photoinhibition and photoregulation. Journal of Biotechnology 194, 91-99. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.12.00

10. Gris B, et al. 2015. Optimizing biomass and high value compound production in Cyanobacterium aponinum PCC 10605. Societa Botanica Italiana. Venezia.

11. Gérin S, et al. 2014. Modeling the dependence of respiration and photosynthesis upon light, acetate, carbon dioxide, nitrate and ammonium in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using design of experiments and multiple regression. BMC Systems Biology 8, 96

12. Hasan R, et al. 2014. Bioremediation of Swine Wastewater and Biofuel Potential by using Chlorella vulgaris, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and Chlamydomonas debaryana. J Pet Environ Biotechnol 5:175. doi: 10.4172/2157-7463.1000175

13. ®antr®®ek J, et al. 2014. Stomatal and pavement cell density linked to leaf internal CO2 concentration. Annals of Botany 114, 191-202

14. Zhang B, et al. 2014. Characterization of a Native Algae Species Chlamydomonas debaryana: Strain Selection, Bioremediation Ability, and Lipid Characterization. BioResources 9(4), 6130-6140

15. Grama B S, et al. 2014. Induction of canthaxanthin production in a Dactylococcus microalga isolated from the Algerian Sahara. Bioresource Technology 151, 297-305

16. Grama B S, et al. 2014. Characterization of fatty acid and carotenoid production in an Acutodesmus microalga isolated from the Algerian Sahara. Biomass and Bioenergy 69, 265-275

17. Miazek K, et al. 2014. Growth of Chlorella in the presence of organic carbon: A photobioreactor study. Conference – Process of Technics 2014 – Prague