大小鼠作为常用的实验室动物,是探索一些情感和动机功能基本机制的理想模型。这些研究主要采用显性行为测量,如动物会靠近获取满足感,反之逃离。而之前的动机和情感状态测量是通过诸如心率、肾上腺酮分泌、或大脑动物等生理指标进行推断的。在此基础之上,可以通过获取动物的超声发生(USV)进行两个方面的行为学研究,一是动物的情感状态,二是动物社交性行为,如交配、育幼、嬉戏、攻击及防卫等),可广泛用于生物医学、神经科学、实验心理学、代谢相关研究等。

2016年8月30日,北京易科泰生态技术有限公司工程师在中科院遗传与发育生物学研究所成功安装调试啮齿类超声(USV)监测系统,该系统可用于基因操作小鼠模型的精神分裂症、自闭症和神经退行性疾病的发病机制研究。

遗传所博士在认真学习仪器数据记录与分析

大鼠超声发生(USV)记录过程

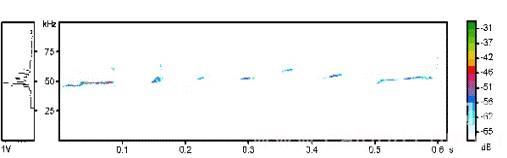

50-KHz USVs超生发生结果

可卡因诱导的50-kHz USVs

需要强调的是,该声谱分析技术可以与动物呼吸代谢技术(包括SSI动物呼吸代谢技术、Promethion动物行为与代谢监测技术)及环境监控因素连用,更全面地监测动物的进食模式、行为谱、动物睡眠活动、运动与代谢、温度心率、动物学习记忆行为、动物情感与动机行为、新陈代谢与影响因子等,还可以与其它更多的动物行为、生理、生物医学仪器连用。

案例1 德国马普鸟类学院科学家采用“SSI动物呼吸代谢技术与USV动物超声发生” 技术,于2013年在国际生理学前沿杂志发表了“Metabolic costs of bat echolocation in a non-foraging context support a role in communication”一文,介绍了蝙蝠发出回声的能量消耗策略,以及USV超声发生在蝙蝠社交通讯中的科学假设。

7只小牛头犬蝠回声与能量消耗相关性

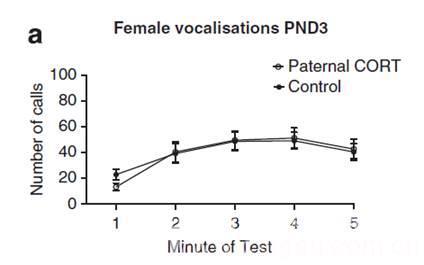

案例2 澳大利亚墨尔本大学神经科学与精神健康研究所科学家采用USV超声发生等技术,于2016年在Transl Psychiatry精神病学杂志发表“Elevated paternal glucocorticoid exposure alters the small noncoding RNA profile in sperm and modifies anxiety and depressive phenotypes in the offspring”一文,主要介绍了糖皮质激素在母体-后代应激诱导特征传递过程中的分子机制。

不同处理条件下的鸣叫次数

部分参考文献:

1. Belagodu A P, Johnson A M, Galvez R. Characterization of ultrasonic vocalizations of Fragile X mice[J]. Behavioural brain research, 2016, 310: 76-83.

2. Carter G G, Wilkinson G S. Common vampire bat contact calls attract past food-sharing partners[J]. Animal Behaviour, 2016, 116: 45-51.

3. Celi M, Filiciotto F, Maricchiolo G, et al. Vessel noise pollution as a human threat to fish: assessment of the stress response in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata, Linnaeus 1758)[J]. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 2016, 42(2): 631-641.

4. Charrier I, Pitcher B J, Harcourt R G. Vocal recognition of mothers by Australian sea lion pups: individual signature and environmental constraints[J]. Animal Behaviour, 2009, 78(5): 1127-1134.

5. Corcoran A J, Woods H A. Negligible energetic cost of sonar jamming in a bat–moth interaction[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 2015, 93(4): 331-335.

6. Corcoran A J, Woods H A. Negligible energetic cost of sonar jamming in a bat–moth interaction[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 2015, 93(4): 331-335.

7. Cordes N, Schmoll T, Reinhold K. Risk-taking behavior in the lesser wax moth: disentangling within-and between-individual variation[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2013, 67(2): 257-264.

8. Dechmann D K N, Wikelski M, van Noordwijk H J, et al. Metabolic costs of bat echolocation in a non-foraging context support a role in communication[J]. How nature shaped echolocation in animals, 2014: 127.

9. Di Stefano V, Maccarrone V, Buscaino G, et al. Experimental procedure for the evaluation of behaviour and biochemical stress of Palinurus elephas exposed to boat noise pollution[J]. 2016.

10. Holt M M, Dunkin R C, Noren D, et al. Are there metabolic costs of vocal responses to noise in marine mammals?[C]//Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics. Acoustical Society of America, 2013, 19(1): 010060.

11. Holt M M, Noren D P, Williams T M. The Metabolic Cost of Click Production in Bottlenose Dolphins[R]. NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION SEATTLE WA NORTHWEST FISHERIES SCIENCE CENTER, 2014.

12. Holt M M, Noren D P, Williams T M. The Metabolic Cost of Sound Production in Odontocete Cetaceans[R]. NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE SEATTLE WA NORTHWEST AND ALASKA FISHERIES CENTER, 2011.

13. Imai R, Sawai A, Hayase S, et al. A quantitative method for analyzing species-specific vocal sequence pattern and its developmental dynamics[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 2016, 271: 25-33.

14. Kim H, Son J, Yoo H, et al. Effects of the Female Estrous Cycle on the Sexual Behaviors and Ultrasonic Vocalizations of Male C57BL/6 and Autistic BTBR T tf/J Mice[J]. Experimental Neurobiology, 2016, 25(4): 156-162.

15. Liska A, Gomolka R, Sabbioni M, et al. Homozygous loss of autism-risk gene CNTNAP2 results in reduced local and long-range prefrontal functional connectivity[J]. bioRxiv, 2016: 060335.

16. Maier E Y, Ahrens A M, Ma S T, et al. Cocaine deprivation effect: cue abstinence over weekends boosts anticipatory 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations in rats[J]. Behavioural brain research, 2010, 214(1): 75-79.

17. Reno J M, Thakore N, Gonzales R, et al. Alcohol‐Preferring P Rats Emit Spontaneous 22‐28 kHz Ultrasonic Vocalizations that are Altered by Acute and Chronic Alcohol Experience[J]. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 2015, 39(5): 843-852.

18. Robillard T, Ichikawa A. Redescription of two Cardiodactylus species (Orthoptera, Grylloidea, Eneopterinae): the supposedly well-known C. novaeguineae (Haan, 1842), and the semi-forgotten C. guttulus (Matsumura, 1913) from Japan[J]. Zoological science, 2009, 26(12): 878-891.

19. Rouse M L, Ball G F. Lesions targeted to the anterior forebrain disrupt vocal variability associated with testosterone‐induced sensorimotor song development in adult female canaries, Serinus canaria[J]. Developmental neurobiology, 2016, 76(1): 3-18.

20. Sauvé C C, Beauplet G, Hammill M O, et al. Mother–pup vocal recognition in harbour seals: influence of maternal behaviour, pup voice and habitat sound properties[J]. Animal Behaviour, 2015, 105: 109-120.

21. Shapiro A D, Slater P J B, Janik V M. Call usage learning in gray seals (Halichoerus grypus)[J]. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2004, 118(4): 447.

22. Short A K, Fennell K A, Perreau V M, et al. Elevated paternal glucocorticoid exposure alters the small noncoding RNA profile in sperm and modifies anxiety and depressive phenotypes in the offspring[J]. Translational psychiatry, 2016, 6(6): e837.

23. Symes L B, Page R A, ter Hofstede H M. Effects of acoustic environment on male calling activity and timing in Neotropical forest katydids[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2016: 1-11.

24. Travis C M G, Genovese R F. Cat-Exposure Results in Significantly More Elicited Alarm Calls (22kHz Ultrasonic Vocalizations, USVs) Compared to Snake-, Ferret-, or Sham-Exposure During a Rodent Model of Traumatic Stress[J]. The FASEB Journal, 2016, 30(1 Supplement): 938.9-938.9.

![聚酰胺粉 [柱层析用,高分离性能] 60-100目/80-120目/100-200目](https://p-06.caigou.com.cn/135x120/2024/7/2024071513085253637.jpg)